GREENVILLE, N.C. (WITN) – Surgeon General Vivek Murthy’s call for a warning label on social media is based on what many call a mental health crisis, not only across the United States but also in North Carolina.

According to the United Health Foundation, here in North Carolina, more than 70% of children with a mental health disorder do not receive treatment. Murthy’s initiative isn’t the only one in the works… The United Health Foundation has put together another initiative with East Carolina University’s Telepsychiatry Program to combat the issue.

Though many factors play into one’s mental health, Pew Research reports that 69% of adults and 81% of teens in the U.S. use social media. Thus, putting a large amount of the population at an increased risk of feeling anxious, depressed, or ill over their social media use.

That’s why the United Health Foundation and ECU are partnering with a new three-year, $3.2 million grant to address the youth mental health challenges in North Carolina.

“There’s a greater need on mental health, particularly given the rising prevalence that we’ve seen here in North Carolina. I think the data is heartbreaking. 9% of our children, ages 3-17 years old have experienced anxiety or depression,” says United Healthcare Community and State CEO Anita Bachmann.

It’s an issue that faces many challenges like a continued stigma attached to having open dialogue, having an open discussion about mental health, and care access due to a shortage in the amount of healthcare, according to Bachmann.

Dr. Sy Saeed North Carolina State Telepsychiatry Program Executive Director says they see over 10,000 children.

“Over 1800 showed a large to moderate level of anxiety, says Saeed. “We are providing both therapy and child psychiatry services.”

This program will help address mental health issues in teens sooner rather than later.

“Most mental disorders start early. As many as 75% of people who have mental disorders would have had their first episode of that illness by age 25. Anxiety, depression, and when people are having difficulty of stress and relationships,” says Dr. Saeed.

Officials say it will create a holistic and effective approach when treating children.

“Mental health for children includes mental, emotional, and behavioral well-being, and that provides the launching pad for how they think, feel, act, and handle stress,” says Dr. Saeed.

Dr. Saeed says the program currently treats 200 children with six clinics in North Carolina but the goal is to expand.

Dr. Saeed and Bachmann say that it’s vital for those dealing with mental health challenges to reach out to their healthcare provider or call the 9-8-8 mental health crisis hotline.

Greenville, N.C. – ECU Health is partnering with Food Lion Feeds, Sodexo and the ECU Health Foundation to provide free meals for kids, teens and people with disabilities as part of the Summer Meal Program. Meals will be available in Greenville, Bethel and Ahoskie. The selected sites this year were chosen based on the need in each county, existing partnerships and the social vulnerability index at each location.

During the school year, many kids and teens receive free or reduced-price meals. When schools close for the summer, those meals disappear, leaving families to choose between putting the next meal on the table or paying for other necessities like utilities or medical care. While over 57% of students in North Carolina receive free or reduced lunch, 66% of Pitt County students and over 90% of Hertford County students receive free or reduced lunch.

Meals will be available until food runs out each day at the following locations:

Greenville: English Chapel Free Will Baptist Church – 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m., Monday-Friday from June 10 to Aug. 23. The location will be closed July 22-26.

Ahoskie: Calvary Missionary Baptist Church – 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m., Monday-Friday from June 10 to Aug. 23. The location will be closed June 19 and July 4-5.

Bethel: Bethel Youth Activity Center – 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m., Monday-Thursday from June 17-July 17. The location will be closed July 3-7.

ECU Health has offered the Summer Meal Program since 2021, providing nearly 12,000 free meals to kids and teens during the summer months. In 2023, 51 ECU Health team members served more than 2,800 meals to kids in need.

No registration is required. For more information about the ECU Health Summer Meal Program, please email [email protected].

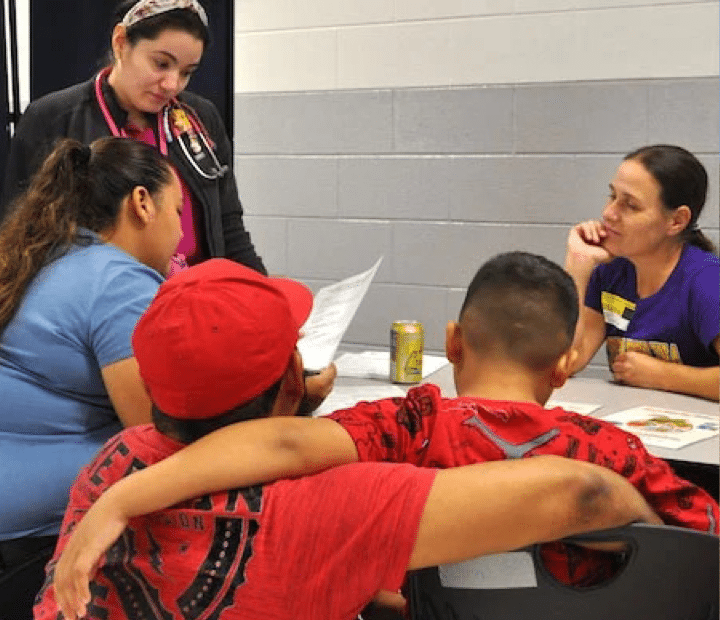

Health care providers of East Carolina University’s Healthier Lives initiative in the Brody School of Medicine continue to use the program to address health care needs for children in rural eastern North Carolina counties and are finding pathways to expand access to care at schools in Duplin County and beyond.

The Healthier Lives at School & Beyond Telemedicine Program originally launched in 2018 to deliver interdisciplinary services virtually to rural school children, staff and faculty during the school day. In response to COVID-19, the program continued to address health care needs for children and expanded access while students were learning remotely.

Since the fall of 2020, the program has used an ECU Transit bus to visit schools in Duplin, Jones and Sampson (Clinton City Schools) counties to provide high-quality health appointments. The retrofitted motorcoach has been used to provide screenings for 303 students, with additional visits planned for existing program partnerships and newly established ones.

The initiative was recognized recently by the Mid-Atlantic Telehealth Resource Center with the Breaking Barriers Through Telehealth Award in the category for small, rural and safety net organizations. During the 2024 Rural Health Symposium, a presentation on Healthier Lives – On the Road Again: Rolling to Reduce School Suspension – was awarded first place in innovations panel.

Experiential learning

Delivering care in the community is also delivering learning opportunities for ECU students. Third- and fourth-year medical students and medical residents participate in clinic days, gaining hands-on experience providing health care to rural populations.

Recent Brody graduate Dr. Melenis Lopez said the Healthier Lives clinics demonstrate that service is truly ECU’s mission. During a school clinic in the fall, Lopez applied pediatric learning experience as a care provider. She collected patient history and assisted in making plans for children that could be passed on to the school.

“Providing care in a place that is convenient to the community can be lifesaving,” Lopez said. “Offering physicals can uncover developmental delays and health problems. Children can’t stay in school without these physicals and proof of vaccinations, so I’m happy we were able to be there for the kids.”

Lopez and her ECU cohort guided elementary students and their families through clinic stations to take vitals, check vision and hearing, and perform physical exams. Students could meet with mental health and nutritional professionals for additional screening when needed.

Lopez used her ability to speak Spanish to help the children feel comfortable and ease the burden on families who may not understand the forms or instructions from the care provider.

Rural health care

Dr. Krissy Simeonsson, associate professor for pediatrics and public health and the medical director for the program, is proud that Healthier Lives is giving ECU students the opportunity to experience health care in a rural setting.

“Students can see that they can help,” Simeonsson said. “Most students and residents we’ve had have that ‘aha’ moment and can see themselves in primary care. They realize they can succeed out here.”

Jill Jennings, ECU’s Healthier Lives program manager, said the hybrid approach of on-site clinics and telehealth makes it easier for the medical providers to communicate with parents in person and more readily make referrals for any nutrition or behavioral health follow-up virtual care.

A $1.2 million grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration funded the first four years of the program. Funding now comes primarily from Anonymous Trust, a private North Carolina foundation, and has been provided by the Harold H. Bate Foundation, the ECU Health Foundation, and the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services Office of Rural Health.

“There are many opportunities for institutions such as ECU to leverage their resources to address community needs,” said Debbie Aiken, executive director of Anonymous Trust. “This initiative is a wonderful example of ECU recognizing health care disparities, and in partnership with a local school district, serving children who might otherwise not receive the care that they deserve.”

Aiken witnessed a program clinic in action at Rose Hill-Magnolia Elementary School in Duplin County. ECU medical students and residents, health sciences undergraduate and graduate students, Healthier Lives team members and partners from the school system and Duplin Health Department screened 47 students who otherwise would have been suspended for not having a health assessment completed by a medical provider.

“These partnerships should be happening across the state,” Aiken said. “Seeing it helps you truly understand the disparities in our rural communities. If more school systems understood that this is available, they would want to participate.”

Community engagement

Dr. Jenelle Brison ’24 said Healthier Lives provided an opportunity for community engagement for medical students. Brison encouraged fellow Brody students to participate.

“It’s so nice to interact with the little kids,” Brison said. “Events like this help break down barriers and offer unique training for students.”

While Brison ultimately hopes to focus on obstetrics and women’s health, she was at ease helping children with vision screenings and demonstrating a blood pressure cuff before taking vitals.

Dr. Bolu Aluko ’24, a Tiana Nicole Williams Scholar at Brody, was drawn to the opportunity for community engagement provided by Healthier Lives.

“Coming into the community is incredibly enriching,” Bolu said. “Every med student should do this. It’s a fantastic way to serve and practice our clinical training.”

Through an interpreter, the family of one student said they had received a call from the school that their son would not be able to return to class because he had not had a physical or proof of vaccinations. They had just moved from Mexico to Warsaw, North Carolina. Without the availability of a Healthier Lives clinic at the school, they would not have had access to a health screening for their son in time to meet the state-mandated deadline.

The family sat with an interpreter and was provided a nutritional referral and a connection to a primary care clinic in Warsaw to establish a medical home. “We’re grateful to know he’s healthy,” his mother said through the interpreter.

“You have to meet people where they are,” Simeonsson said. “A lot of families trust the school. When you see the families getting help for their children, you know the program is living up to expectations.”

Dr. Michael Granet has provided more than patient care and dental instruction as an adjunct assistant professor at the East Carolina University School of Dental Medicine’s community service learning center (CSLC) in Brunswick County.

Through gifts totaling more than $100,000, Granet has invested in and helped the school obtain state-of-the-art equipment for the CSLC. Granet, the staff and dental students at the CSLC now have access to a cone beam computed tomography (CBCT)/panoramic X-ray unit, which provides 3D imaging; a TRIOS intraoral scanner and CoDiagnostix software; and a 3D printer. The cutting-edge equipment allows the care team to provide scans for dental imaging instead of having to take impressions.

“Technology is at the forefront of dental education now more than ever before, and Dr. Granet’s gift of this state-of-the-art equipment provides our students and residents with vital exposure to digital dentistry,” said Dr. Greg Chadwick, dean of the dental school. “This gift, coming from a part-time faculty member, leverages our ability to expand the scope of care for the communities we serve.”

Dr. Dianne Caprio, clinical assistant professor at ECU and director of dentistry at the Brunswick CSLC, said dentists can create a virtual model of patient’s teeth or print the model if needed.

“Dentistry has gone digital, and we are just scratching the surface of all the possibilities,” Caprio said. “Having this equipment offers the students and residents an introduction to the digital dental world.”

Caprio said the new equipment allows staff the ability to design crowns, dentures and other prosthetics on the software and print them in the office. “We can plan for accurate placement of implants using the CBCT, TRIOS and the CoDiagnostix software by designing surgical guides and printing them in house,” she said.

Granet learned about the CSLC after moving to Wilmington from Maryland. He works at the center each Tuesday caring for patients’ periodontic and implant needs and serving as an instructor for the dental residents working there.

“I made donations to the clinic so this equipment could be here and we could all use it and patients could benefit from it,” Granet said. “All I did was give the money. What I get back is much greater than the money I give. I am in a happy place when I get here (Brunswick CSLC) on Tuesday.”

Staff at the CSLC honored Granet for his support with a plaque at the center. Caprio said the upgrade in technology is important to the CSLC, but Granet’s “greatest gift is his time and dedication to teaching the residents and students.”

In a ceremony more festive than formal, fourth-year medical students in the Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University learned March 15 where they will spend the next three to seven years completing residency training.

This year, 100% of Brody’s 79 members of the Class of 2024 — which began its medical school journey during the COVID-19 pandemic — matched with a residency program.

The traditional event is arguably the pinnacle of the medical school experience for Brody students. Before they opened their envelopes to reveal their next stop, the students were presented to the audience of family, friends and members of the Brody community to strains of music they each selected as they marched — or danced — across the stage in the ballroom of ECU’s Main Campus Student Center.

“Match Day is such a special time for these students from the Brody School of Medicine, all of whom have worked incredibly hard to reach this exciting moment,” said Dr. Michael Waldrum, dean of Brody and CEO of ECU Health. “Our medical students, by virtue of the education they receive here at Brody, are uniquely prepared to provide high-quality, human-centered care to the patients they will soon serve as part of their residency training and beyond. I want to extend a heartfelt congratulations to the Brody Class of 2024. We are grateful for the positive impact they will have on the lives of so many.”

Dr. Jason Higginson, executive dean of the Brody School of Medicine, said the class of 2024 represents Brody’s mission — a diverse group of students who come from all parts of the state, who will largely return to serve North Carolina as doctors.

“We have a 100% match rate, well above the national rate, which is also a testament to our faculty and staff,” Higginson said. “About 50% of our graduates are staying in North Carolina, which is our primary mission, and about 20% are staying locally.”

One of Brody’s secondary missions is getting future doctors to practice primary care, and half of the class of 2024 have committed to being on the front lines of health care.

“They are great kids. It’s one of our best classes ever,” Higginson said.

A perfect match

Before he even knew the mission carved out by the Brody School of Medicine to reach underserved patients and address health disparities, Connor Haycox was intent on improving lives.

During his undergraduate years at Davidson College, Haycox volunteered and interacted with patients from underserved communities and saw himself as a future physician to help bridge gaps in care.

“I wanted to go into medicine to help address that,” said Haycox, a native of Chapin, South Carolina. “I could see myself as a primary care physician; I figured I could do the most good for people on the front lines.”

Haycox matched in family medicine at ECU Health.

“I know this is where I’m supposed to be,” he said.

After college, Haycox spent two years completing a MedServe fellowship — an AmeriCorps program through which fellows assist in key primary care services and engage in community health work including outreach, education and other projects that impact community health. During the fellowship, Haycox worked in a rural family medicine practice in Benson, North Carolina, where he witnessed “the breadth of the problems patients presented,” he said. “I wanted to be able to meet them in their particular situation and help them maximize their health goals. I really started to see myself in that role.”

By the time Haycox was ready to take on medical school, he knew Brody was the place for him. His goals and his philosophy naturally aligned with the school’s mission, making it a perfect fit.

“The mission of Brody to develop family medicine doctors to serve the state was really a natural transition for me,” he said. “It just made the whole process that much more streamlined. I saw myself here from the start.”

Haycox sees himself serving eastern North Carolina long term — especially since his wife, Dr. Natalie Malpass, a 2022 Brody graduate, is completing a family medicine residency with ECU Health. The two met during Haycox’s stint in Benson, and that experience has cemented his view of medicine as part of teamwork and partnership.

“I think it’s invaluable to have a partner in medicine,” Haycox said. “It’s such a challenging field and an emotional investment, and I feel like having someone to be able to talk to about the things you see has helped me professionally, but it’s more just being able to walk through life with someone who understands.”

Working with the Benson clinic to respond shortly before medical school to help the team coordinate the practice as a COVID-19 testing site also showed him the importance of taking unforeseen circumstances and transforming them into something meaningful.

“Medicine is personal, and we adapt,” Haycox said. “We do that because we need to for our patients. The pandemic was a whole learning process, and it taught me that we may not have all the answers, but we can learn with our patients how to best come out.”

Navigating the pandemic with his classmates also taught him lessons about adaptation, appreciation and taking advantage of opportunities that presented themselves over the years. Haycox served as an anatomy tutor and was part of Brody’s Medical Education and Teaching Distinction Track cohort — which prepares students to be effective medical educators and develops their interest in academic medicine.

“I can see myself going into academic medicine in the future, so I wanted to develop those skills,” he said.

As for the culmination of his Brody experience, Haycox is excited to celebrate his next step alongside his family. For him, Match Day is the beginning of a new adventure in primary care and family medicine.

“Medical school is a long haul, so I’m excited to celebrate with my family,” he said. “Today, all of this kind of becomes more real.”

From motherhood and maternal medicine

For most medical students, finding out where they will complete their residency during Match Day is plenty to celebrate. For Ahoua Dembele, that’s just the start of the day’s festivities as her family is in town for an equally joyous celebration: a baby shower for her third child, due in just four weeks.

Dembele moved with her family from her home in Ivory Coast to Senegal, then attended boarding school in France. She returned to Africa’s north coast, this time Tunisia, with her family for six years before finally settling in Charlotte after graduating high school in 2011.

When Dembele arrived in the States, she had some measure of command of a number of languages – French, Arabic and an understanding her first language, Dyula, a dialect of Mande, but she didn’t speak English. She enrolled at Central Piedmont Community College for a crash course in a new language and started her educational journey.

After a few years at the community college and managing a pizza restaurant, she transferred to UNC Charlotte, where she graduated with a degree in biology because she was always fascinated with science.

She soon had her first son and worked for a while as a medical assistant in a doctor’s office in Charlotte.

Dembele was accepted as a medical student at Brody just before the COVID-19 pandemic complicated just about every aspect of life – especially education. The disconnected learning was tough, but she excelled, especially in light of having her second son just before starting school and getting married to her long-time partner who was frequently out of the country for business.

“I started medical school when my oldest was 2 or 3 and my youngest was 1. Daycare regulations were a little weird and my school was, too. We couldn’t go to Brody because of COVID, so I had to find ways to study,” Dembele said.

Her mother stayed with her to help with the boys and when her husband was home “he would do everything so that I could find places to study, but it was hard because they still need their mom, so I had to find ways to at least do bedtime every day.”

Dembele matched to undertake her residency in obstetrics and gynecology at ECU Health. She wants to make a difference in the lives of mothers and babies, especially after witnessing health conditions in eastern North Carolina through her clinical rotations. She hopes to sub-specialize in maternal and fetal medicine.

“Something about pregnancy has always attracted me. It’s miraculous, phenomenal, that a body can do that,” Dembele said. “It’s mind blowing. I’ve seen a lot of deliveries, but I’m always amazed, every time, even at my own.”

She credits Dr. Jill Sutton, a clinical associate professor at Brody who specializes in obstetrics and gynecology, with invigorating her desire to focus on pregnancy and women’s health.

“The first time she taught us she was so bubbly, so excited and so joyful when she was talking about pregnancy,” Dembele remembered. “Her enthusiasm, her devotion. I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is who I want to be.’ She’s been a mentor for a long time, and I hope to stay here and continue to train with her.”

At Match Day, Dembele was joined by her husband, her boys and her mother, who traveled from Wisconsin, where they now live. She beamed with pride amidst a family that had travelled so far, and made real sacrifices, to stand with Ahoula as she tore open the envelope that revealed where the next few years of their lives would play out.

Dembele will have a few weeks with her newest child before starting residency as she and her husband planned — calculated — the pregnancy meticulously.

She is a scientist, after all.

‘That’s the kind of doctor I want to be’

The few minutes it takes for the National Resident Matching Program’s mathematical algorithm to match applicants and programs across the country can be daunting for many medical students to think about — but for Emmalee Todd, reflecting on those fateful moments feels a bit zen.

“I think that no matter where I end up, I will find a way to be happy and fulfilled and feel like I’m moving in the direction I want to move in,” Todd said. “I feel like regardless of where I have ended up, I’ve been able to find my own path in that setting.”

And they will do it again.

Todd, who crossed the stage to the inspiring lyrics of Shakira’s “Try Everything” from the movie “Zootopia,” was joined by their parents and girlfriend Friday as they opened their envelope to reveal that they matched in internal medicine and pediatrics — known as “med-peds” — at the University of Maryland.

“I’m really excited,” Todd said. “Maryland made a really good impression on me. I’m excited for it.”

Todd’s journey through medical school was inspired by leadership experiences, bonding with fellow students and learning to adjust to what comes in ways that ensured not only success but a lesson to carry with them into the next chapter. A member of Brody’s first class to begin medical school under “pivoted” protocol because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Todd said their class made up for lost time later.

“For most of us, 2020 was pretty lonely,” they said. “We were thrown into this whole new level of work and new level of stress, and we wanted to be able to lean on our classmates.”

The Class of 2024 leaned into the changes, however, and started forming bonds as they interacted during some classes and labs and outside of school. Those bonds have stood the test of time and have been a vital part of Todd’s experience — which really began when they were an undergraduate at Northeastern University in Boston studying behavioral neuroscience.

Todd became an emergency medical technician and got a firsthand look at medical care — after getting a taste of the health care field over the years from their mother, Dr. Karen Todd, a pediatrician and Brody alumna herself. That exposure, coupled with making friends from all over the country and world, helped lead Todd toward a career in health care.

“I was meeting people from places I’d never been before,” they said.

After working for two years as a medical assistant, Todd brought that same energy to Brody, where they could see themselves as part of a smaller class.

“It really came down to the vibes,” they said. “It was one of the few places I interviewed where I felt a connection to the people, students and faculty right away. I could see myself here.”

Todd has thrived, taking on leadership roles including class diversity representative, executive treasurer and vice chair on the Medical Student Council, an elected organization that represents the medical student body as a voice in education, political and social interests.

“I got nominated our first year and decided I was going to run,” Todd said. “I got elected, and there I was. When you’re asked for your input, it’s because someone thinks your input is valuable. It is an honor, the trust [my classmates] have placed in me to be a voice for my class, to speak up and advocate for changes, policies and guidelines that are going to improve or rectify parts of our experience.”

Todd, who was drawn to med-peds because of an experience during a third-year rotation.

“I was trying to be open-minded, though I initially thought I wanted to do emergency medicine,” Todd said. “During my internal medicine rotation, I spent two weeks in the med-peds clinic and fell in love with the feel of it, with the attendings and residents and their personalities and the way they thought about medicine and approaching their patients. The more I got to interact with them, the more it reinforced that that’s the kind of doctor I want to be. They were passionate about trying to do the right thing for their patients.”

Drawing upon every memory and experience they gained along the way — from undergrad to Match Day — Todd is ready to embrace the next step and to take advantage of all the lessons waiting on the horizon.

“I thought when I was in undergrad that I wanted to get my Ph.D.,” they said. “I love neuroscience; I loved feeling like I was on the cutting edge of the frontier of knowledge, pushing into something that people have never known about before. But the more I got into the clinical environment, I really liked the detective work aspect of medicine, the team feel of it. All of the members of the health care team bring their own skills to the table but have the same goal, which is making the patient better.”

Like many health professionals who treated patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, Drs. Paul Bolin and Paul Shackleford started to draw conclusions about who was most at risk of dying from infections: people with eastern North Carolina’s typical comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes and obesity.

Shackleford, a primary care provider and research professor at the Brody School of Medicine, said large swaths of the population served by the heath care structure in eastern North Carolina can be identified through electronic medical records. But that is just part of the equation, leaving a sizable percentage of citizens outside of public health surveillance.

“We started having people novel to our system who were coming into the hospitals, which gave us the idea that maybe we should start looking for people to figure out a mitigation strategy,” Shackleford said.

At the height of the pandemic, Shackleford and a team of health care professionals — Bolin, a fellow Brody professor and chairman of the department of internal medicine, and Dr. Linda Bolin, an associate professor of nursing science in the College of Nursing with expertise in hypertension, and Dr. Ashley Burch, an assistant professor and behavioral health scientist in the College of Allied Health Sciences — were getting requests from businesses across the region to help find ways to keep workplaces functioning and employees safe on the job.

“I don’t have any industrial hygiene or occupational health credentials, but when somebody calls, we have to help” Shackleford said. “One business owner called from his hospital bed recovering from COVID. His business was identified as critical infrastructure, so they were up and running, or trying to run, and struggling because they had employees who were out of work.”

Shackleford said they “didn’t do anything magical” besides reiterating the established guidelines. But having direct contact with workers who likely weren’t getting routine medical care and under public health surveillance spurred Shackleford and the Bolins to consider how they could be proactive in finding citizens with chronic illnesses. The COVID-19 pandemic would eventually subside, but the unhealthiness of rural Southern lifestyles was here to stay. How could they be part of stemming the tide of disease caused by diet and lifestyle choices?

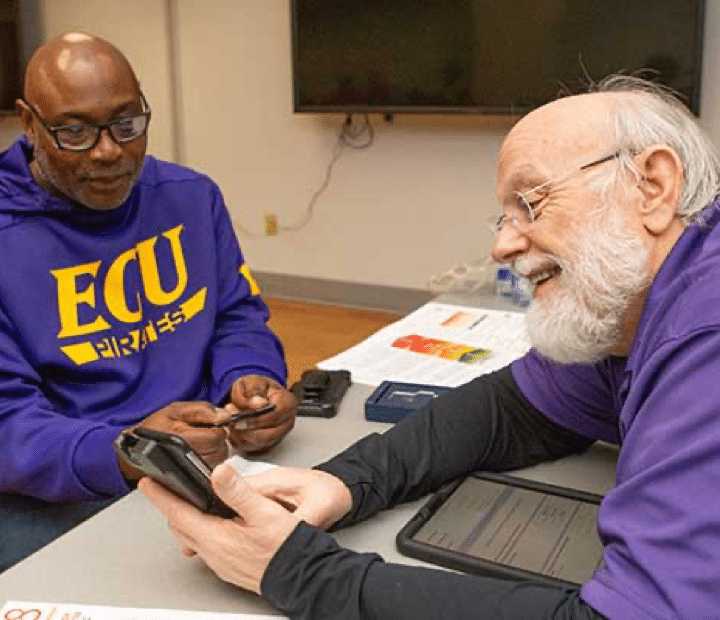

The team inaugurated the SERVIRE (Stopping Early Reversible Vital organ damage In Rural Eastern North Carolina) project and decided that incorporating students into outreach efforts would fulfill ECU’s motto, and overarching mission, of service.

To date the SERVIRE project has worked with more than 35 businesses across eastern North Carolina, having engaged nearly 1,400 workers at job sites ranging from a water faucet manufacturer in New Bern to a metal fabrication shop in Ahoskie and a commercial fishing fleet on Hatteras Island.

Researchers initially envisioned more interaction with farm workers, but enough of the potential study participants were undocumented, and reticent to participate, that study directors refocused their efforts to more traditional manufacturing businesses. While they were able to reduce operating cost and complexity, and deal with the privacy issues, the question of why 20-25% of workers flatly refused to be part of the study shifted the focus of the team’s research.

“We have folks that know how to run focus groups sit down and actually ask them, ‘What’s the problem?’” Shackleford said. “Early on in COVID we pivoted to delivering vaccines to individuals who would not go to mass vaccination sites, and it was a similar cohort. Yet they were welcoming of the one-offs that we were able to offer. We didn’t do a lot of vaccines, but we still got in the door.”

Hesitancy would be a continuing challenge, Shackleford knew, but it was better in his mind to achieve what could be achieved to keep small towns in the region from folding.

The Bolins and Shackleford recognize that providing health care to rural communities relies on vibrant and resilient businesses that support the functioning of small, rural communities. Without well-paying jobs, hospitals and community clinics run the risk of losing resources or shuttering altogether.

“If we can keep industry running, we can keep this community fed,” Shackleford said.

Reaching Underserved Communities

For Dr. Linda Bolin, who has advocated for heart health for many years, educating patients on health-promoting lifestyle changes wherever she can is important.

“Some companies, like Moen, want us back all the time, and it gives us an opportunity to talk to them and ask, ‘Well, what changes have you made?’” Bolin said. “It heightens their awareness to know we are going to come back. Sometimes you have to hear things more than once, like with students, you have to repeat it several times for the idea to click.”

Bolin said diet and movement are a huge part of the problem for eastern North Carolina. People who seem relatively healthy because their young bodies can mask systemic health issues might actually be ticking time bombs, health-wise.

“During the Vietnam War we had 18-year-olds dying, and when autopsies were done, they were already suffering from atherosclerosis. Establishing healthy habits and making behavioral changes early in life, before age 20 is crucial,” Bolin said. She stressed that the workforce is often seemingly young and robust but shows signs of unhealthiness from eating fast food and being too exhausted from a 12-hour shift in a manufacturing facility to want to exercise.

“These conditions can take a toll on the body, especially for those with a family history of cardiovascular disease, leading to the onset of pre-hypertension,” Bolin said. “We see a significant number of people with hypertension who are already taking maximum medication doses, leading to a classification of resistant hypertension.”

Bolin likened this situation to developing tolerance to antibiotics after prolonged use — if individuals with resistant hypertension develop severe infections such as sepsis, standard antibiotic treatments may become less effective.

Meloney Quay, a Moen employee from New Bern, said she values the SEVIRE outreach because it’s hard to get in to see a primary care doctor and she usually only seeks medical care in emergencies. She would like to see a clinic at her job site twice a year to keep tabs on her basic health information.

Sapphire LaCoss, who also works on the Moen manufacturing line, said she first participated in the SERVIRE research project because it helped lower the cost of her health insurance. Because both her mother and grandmother are diabetic, she feels a responsibility to keep on top of testing.

“I have four kids. I play football, soccer, basketball and volleyball. I help cheerleading. I like to stay healthy,” LaCoss said. “[The Moen leadership] realizes that we work from 5:30 until almost 4 every day and we don’t have time to go to the doctor, right? I think it’s important that they think that their employees are taken care of and they’ll help us because it keeps us healthy and keeps the business going.”

Brooke Rose runs Rural Carolina Ambulance Service with her husband in Ahoskie and is contracted to do the testing for the research project. She said she gets a lot of satisfaction from helping to identify workers’ health concerns.

“We’ve caught very high blood pressure or that they are diabetic and didn’t know they had it. Then they can get the help that they need,” Rose said. “We’ve seen them later and their levels were down, their blood pressure is better and they’re very appreciative. They’re grateful.”

Teaching Students

SERVIRE is formally a research project, working to establish best practices for how to identify workers who have fallen through the cracks of the health care system. But the project leaders have turned it into a teaching opportunity — students and contracted medical workers assess workers for basic health metrics that can identify precursors for serious medical complications: height and weight, body index, neck circumference and basic blood sugar readings.

The research is important for the immediate health of the individuals who are tested, and the study directors hope their work will impact regional health in the long-term, but the outreach efforts also give ECU students hands-on experience working with the high-risk populations they will serve after graduation.

Linda Bolin and Burch offer an Honors College seminar for pre-nursing and health majors that focuses on chronic diseases in eastern North Carolina and provides students with the opportunity to participate in the SERVIRE project.

Their seminar, titled “Ghosting Premature Death: Promoting Prevention in Eastern North Carolina,” emphasizes the importance of early engagement with health-related majors by exposing potential students to population health issues and social determinants of health.

“Having these students, along with pre-medical and pre-nursing students, volunteer as integral members of the team is essential because it recognizes the significance of investing in future doctors, nurses and other health care workers, instilling in them a sense of service to their community,” Linda Bolin said.

Several students who were enrolled in the Honors College seminar as pre-nursing majors are now first semester students in the College of Nursing.

Kaylee Ontiveros, an Honors College nursing student from Ayden, said it was eye-opening for her to see just how far from primary care options many of the workers were, and how having hands-on experience with patients can tie together book learning and classroom lectures.

“A lot of people struggle to get medication or get to the hospital compared to places like our city, where can get to doctors right down the road,” Ontiveros said. “We saw a patient who had an abnormality in her neck that she didn’t know about. We said, ‘OK, you need to check this out,’ so it was really putting everything from classroom into perspective.”

Gracyn Faulk, a fellow Honors College nursing student from Goldsboro, participated in research visits to a call center in Greenville and a soup kitchen. She agrees that having an opportunity to interact with real patients was a benefit to her education.

“It’s not what I expected. I’m not really sure what I expected. But it was good to see some of the social determinants of health that we talk about in class, to see them in real life. Some of the people had stories that you wouldn’t hear otherwise,” Faulk said.

Gracie Ipock, a first semester Honors College nursing student from Morehead City, was with Faulk. She said being in the community and learning about people was a huge benefit. Ipock had previously worked as a certified nursing assistant, but this was a new way to interact with patients.

“I think it will help me to be better at clinicals like now because I’m able to talk to these people and not be so scared,” Ipock said. “The more confident you are with working with them, the more they’re going to feel relaxed. Someone could look perfectly fine and not know that they have a lot of issues going on with their health.”

When East Carolina University’s new Farm 2 Clinic (F2C) mobile teaching kitchen and pantry hits the road it will deliver more than nutrition to underserved people in the region. The 28-foot trailer, wrapped in bold purple, with imagery of colorful produce and program logos, also carries the university’s values.

“I am struck by how this is a mobile billboard for ECU’s mission of student success, public service and regional transformation,” said Christopher Dyba, vice chancellor of university advancement. “I cannot help but have a bit of awe seeing this and want to take a moment to say how impressive and beautiful this is.”

The mobile teaching kitchen and pantry launched Tuesday at a ribbon cutting and celebration at the College of Allied Health Sciences. Through its hunger-relief platform, Food Lion Feeds, Food Lion invested $150,000 in ECU’s innovative F2C initiative to make the trailer possible.

“Today’s event celebrates a longtime and meaningful corporate partnership with Food Lion,” Dyba said. “Together, we share an important commitment to ending hunger and addressing health disparities in our local communities.”

Dyba also recognized Duke Endowment, which provided programmatic support for the Department of Nutrition Science to manage the Fresh Start program, and Camping World and Signsmith for their efforts to outfit and design the trailer.

Through the Food Lion partnership, the mobile teaching kitchen and pantry is equipped with two commercial refrigerators, shelving, sinks, spaces for food preparation and cooking, and extensive storage for educational supplies. At the ribbon cutting, the trailer also was loaded with hundreds of pounds of fresh produce donated by Food Lion. The produce will be provided to patients at the Pitt County Care Clinic, run by Dr. Tom Irons, and the Hope Clinic in Bayboro.

The mobile teaching kitchen and pantry is designed to improve access to healthy food and support improved nutrition and health for uninsured, low-income diabetes patients in rural eastern North Carolina. The program provides nutrition science students experience as they guide patient participants to learn food skills while enabling them to provide fresh, local produce to patients directly.

David Garris, director of operations with Food Lion, said the company supports ECU’s Farm 2 Clinic initiative because of its transformative approach to addressing food insecurity.

“We applaud ECU and the work you’re doing. We’re honored to be a part of and support your mobile teaching kitchen and pantry,” Garris said. “Now more than ever, unique approaches and collaborative partnerships, like the one we have with East Carolina University, are needed to address food insecurity. Together, we are meeting our community’s needs by increasing access to fresh and nutritious food and addressing the root causes of hunger.”

The partnership with ECU carries a personal element of pride for Garris, who describes himself as loyal and bold, purple and gold.

“To say that I am proud of East Carolina might be an understatement. I am incredibly proud to support their efforts. As a former student of East Carolina University, where I studied music education, I was a proud Marching Pirate and have always felt a sense of belonging,” Garris said. “We love this university, and even more so, we love what this university means and does for eastern North Carolina.”

Dr. Michael Wheeler, chair of the nutrition science department, described the new mobile kitchen as a celebration of three Ps — the right people, project and partnership

The idea of a program to take nutrition science into the field was discussed for years within the department. He said it became reality when Dr. Lauren Sastre, assistant professor and founder and director of the F2C initiative, created the project. Sastre and F2C graduate students leaders recruited more student volunteers to implement the program. By establishing partnerships in the community more people became involved and supported the initiative.

At Hope Clinic in rural Pamlico County, Executive Director Yolanda Cristiani and staff provide primary health care to low-income, uninsured adults. Cristiani heard a presentation on ECU’s Fresh Start program and applied to participate.

“From the health coaching to the diabetes education and exercise, and the nutrition aspect, this program exceeded my expectations,” she said. “One (program graduate) lost a considerable amount of weight, gained confidence, got a job, and now we see him outside the grocery store he now works in, swinging a kettle ball on his breaks. This has really changed his life in a lot of ways.”

Cristiani said she sees many positive results of the Fresh Start program in her community. Patients have included their family members and shared the lifestyle changes and nutrition lessons at home. She said the addition of a mobile teaching kitchen and pantry will significantly boost their support of marginalized communities.

Brandon Stroud ’21 ’23, F2C’s assistant director, is completing his dietetic internship with ECU and plans to be a registered dietitian. His career path has been influenced by working in the community with Fresh Start and watching F2C grow.

“This program was my first exposure to community-engaged nutrition research and programming and changed my career trajectory as I want to continue to find innovative ways to work in and serve eastern North Carolina,” Stroud said. “One highlight for me was a patient whose blood sugar was so high it had started to affect his vision, and he told us that after the program he was able to see better.”

Stroud said much of the program’s success was generated by the involvement of more than 200 students who contributed 200,000 volunteer hours, participated in 23 student research projects, and assisted in developing 14 national peer-reviewed scientific presentations and publishing five peer-reviewed manuscripts.

“We are not only serving eastern North Carolina, we are showing the rest of the United States how to do food and nutrition programming in novel ways,” Stroud said.

Brooke Gillespie ’23, F2C coordinator and a nutrition science graduate student, began as a volunteer with the Fresh Start program in her junior year.

“At that time, I was so beyond excited to get my foot in the door with a program that represented ECU and the eastern North Carolina community. Little did I know, I was stepping into a world that would completely change my life,” Gillespie said.

During her earlier involvement in Fresh Start, Gillespie said Sastre took her under her wing and trusted Gillespie with food preparation and recipe development, vital components that keep the program running. Thanks to Food Lion, she said, program components will be managed with ease using the mobile kitchen.

“I can tell you that our impact is far beyond what numbers can represent. I have been able to watch students go from shy, nervous and unsure of their abilities into being some of the most self-assured, confident and driven future health care professionals,” Gillespie said. “I have listened to patients who have told me how this program has helped them face barriers they never thought they would overcome. I even had a patient tell me how when she started the Fresh Start program she thought that diabetes had control over her life, but now she knows that she has control over her diabetes.”

ECU’s Pursue Gold campaign to raise half a billion dollars will end in December. This ambitious effort will create new paths to success for Pirates on campus, across the country and around the world. Donor gifts during the campaign will keep ECU constantly leading and ready to advance what’s possible. Learn more at ECU’s Pursue Gold.

ECU Health is celebrating 20 successful years of the Community Benefit Grants Program which was created in 1998 as a joint partnership between the health system and the ECU Health Foundation to address the health and wellness of Pitt County residents. As the health system grew, the grants program expanded to include the regional hospital service areas, as well. The overall goal of the program is to help people before they reach the point of being hospitalized for health conditions that could otherwise have been avoided.

“ECU Health feels one of the best ways to empower people to be active partners in their own health care is to provide them with the education and tools needed to prevent and manage chronic disease,” said Dr. Michael Waldrum, CEO, ECU Health. “This is accomplished through establishing community partnerships with local non-profits. The grants program provides these organizations with financial support to develop and implement programs that provide: early detection of chronic illness, education on wellness and prevention strategies, community health initiatives, and health care services directly in the communities where people live.”

Since 1998, $30.4 million has been distributed to 1,670 grant recipients. These funded programs have improved the health and quality of life for countless residents of eastern North Carolina.

“People across eastern North Carolina have benefited from all of the funded initiatives. Programs take place in civic centers, community gardens, Boys and Girls Clubs, churches, schools, senior centers and other community venues,” said Brian Floyd, president of ECU Health Medical Center and chief operating officer of Vidant Health Hospitals. “The grants being funded help remove financial and transportation barriers in receiving health education and direct health services in rural communities. We are reaching well beyond the walls of our hospitals to care for the people in our region who need it most.”

This year, ECU Health is distributing $1.9 million to 160 grants for communities in eastern North Carolina for the 2016-2017 grant cycle. Grants are administered by the ECU Health Foundation and awarded to programs that focus on chronic disease prevention and management, nutrition and physical activity, and improving access to care.

Media contact: Beth Anne Atkins, director, marketing and communications, ECU Health Foundation, 252-847-7695 or [email protected]

SUMMARY

| ECU Health Hospital | # of Programs Recommended for Funding | Dollars Recommended |

# Estimated to be Served |

# Estimated to be Financially Needy |

| Beaufort | 18 | $100,000 | 21,021 | 15,533 |

| Bertie | 14 | $102,250 | 18,496 | 17,606 |

| Chowan | 22 | $107,430 | 19,269 | 7,186 |

| Duplin | 12 | $102,000 | 23,125 | 19,167 |

| Edgecombe | 14 | $106,000 | 6,625 | 5,445 |

| Outer Banks Health | 8 | $110,000* | 4,219 | 4,219 |

| Roanoke-Chowan | 13 | $100,000 | 12,054 | 9,554 |

| Total Regional | 101 | $727,680 | 104,809 | 78,710 |

| ECU Medical Center | 59 | $1,182,350 | 402,549 | 216,923 |

| Overall Total | 160 | $1,910,030 | 507,358 | 295,633 |